Page 51 - DreamScapes Magazine | Spring/Summer 2024

P. 51

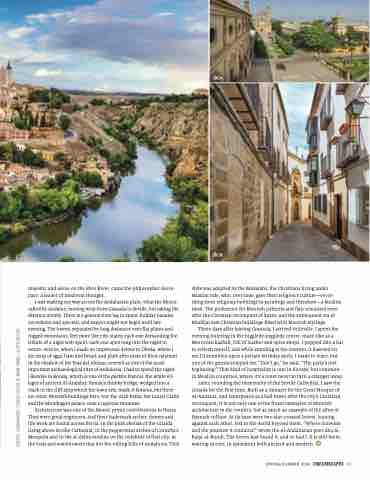

ÚBEDA

ÚBEDA

majestic and alone on the Ebro River, came the philosopher Avem- pace, a leader of medieval thought.

I was making my way across the Andalusian plain, what the Moors called Al-Andalus, moving west from Granada to Seville, but taking the distance slowly. There is a general time lag in Spain; holiday parades are solemn and spectral, and supper might not begin until late evening. The towns, separated by long distances over flat plains and rugged mountains, feel more like city-states; each one demanding the tribute of a night well spent, each one open long into the night in return. And so, when I made an impetuous detour to Úbeda, where I ate soup of eggs, ham and bread, and plate after plate of fried calamari in the shadow of the Eras del Alcázar, revered as one of the most important archaeological sites of Andalusia, I had to spend the night. Likewise in Ronda, which is one of the pueblos blancos, the white vil- lages of ancient Al-Andalus. Ronda’s chunky bridge, wedged into a crack in the cliff atop which the town sits, made it famous, but there are older, Moorish buildings here, too: the Arab baths, the Laurel Castle and the Mondragón palace, now a regional museum.

Architecture was one of the Moors’ prime contributions to Iberia. They were great engineers, and their trademark arches, domes and tile work are found across Iberia: in the pink obelisk of the Giralda rising above Seville Cathedral, in the peppermint arches of Córdoba’s Mezquita and in the al-Zahra medina on the outskirts of that city, in the forts and watchtowers that dot the rolling hills of Andalucía. This

style was adopted by the Mozarabs, the Christians living under Muslim rule, who, over time, gave their religion’s culture—every- thing from religious buildings to paintings and literature—a Muslim twist. The preference for Moorish patterns and flair remained even after the Christian reconquest of Spain, and the subsequent era of Mudéjar saw Christian buildings fitted with Moorish stylings.

Three days after leaving Granada, I arrived in Seville. I spent the evening loitering in the higgledy-piggledy centre, maze-like as a Moroccan kasbah, full of leather and spice shops. I popped into a bar to refresh myself, and while standing at the counter, it dawned on me I’d stumbled upon a private birthday party. I made to leave, but one of the guests stopped me. “Don’t go,” he said. “The party’s just beginning!” That kind of hospitality is rare in Europe, but common in Muslim countries, where it’s a tenet never to turn a stranger away.

Later, rounding the immensity of the Seville Cathedral, I saw the Giralda for the first time. Built as a minaret for the Great Mosque of Al-Andalus, and repurposed as a bell tower after the city’s Christian reconquest, it is not only one of the finest examples of Moorish architecture in the country, but as much an example of the alloy of Spanish culture. At its base were two star-crossed lovers, leaning against each other, lost to the world beyond them. “Where is Seville and the pleasure it contains?” wrote the Al-Andalusian poet Abu al- Baqa’ al-Rundi. The lovers had found it, and so had I. It is still there, waiting as ever, in splendour both ancient and modern. DS

PHOTOS: SEAN PAVONE | TOURIST OFFICE OF SPAIN | MIGEL | SHUTTERSTOCK

SPRING/SUMMER 2024 DREAMSCAPES 51